Tags

Facebook Fan Page, Memory for the Future, Miejsce Pamięci Zagłady Blisko Nas, Pamięć dla Przyszłości, Places of Holocaust Memory Near Us, Włocławek’s Forgotten Street, Włocławska Zapomniana Ulica

“Here and then” (“Tu i wtedy”)…that was the recurring line in Deputy Mayor Robert Dorna’s speech at the unveiling of the lapidarium in the Jewish cemetery in Wronki in December 2014. He linked the place we were standing (tu—here) to various moments in history (wtedy—then).

This could be an apt description of many of the heritage projects I have observed. They are efforts to gather together the fragments that can be recovered, and to reassemble them so they bring back to everyday landscapes the memories of multiple historical events in the lives of former Jewish residents. Seeing the past in the present has also been the touchstone of my recent trip to Poland. Everywhere, it seemed I was walking through streets as they look today, and at the same time carrying envisioning the way they looked back then (wtedy). Linking a particular place concretely to its past was also the goal of the contest that led the students and teachers at the Automotive High School in Włocławek (Zespół Szkół Samochodowych im. Tadeusza Kościuszki) to develop their Facebook “fan page” Włocławek’s Forgotten Street (Włocławska Zapomniana Ulica). They decided to focus on Piwna Street, which despite its small size (just two blocks long) became a focal point for viewing Jewish life and death in this city.

Włocławska Zapomniana Ulica–the Facebook fanpage documenting the history of Włocławek’s Jews, on Piwna Street and beyond.

For thirteen years, the program “Memory for the Future” (“Pamięć dla Przyszłości”) has held annual contests for middle and high school students, challenging them to explore some aspect of Holocaust history. Initiated by the Association of Children of the Holocaust in Poland, and joined in recent years by the Polin Museum, Jewish Historical Institute, and Center for Educational Development, students have produced a variety of projects—essays, posters, and drawings. This year, the sponsors decided to try something new, more in keeping with the way young people communicate today. That’s why this year’s challenge “Places of Holocaust Memory Near Us” (“Miejsce Pamięci Zagłady Blisko Nas”) involved the production of a Facebook page.

Włocławek is a city of about 114,000 residents; the population has been declining since the fall of state socialism as local industries have closed and residents have sought better opportunities in more prosperous places within and outside of Poland. A century earlier, the city experienced rapid growth; during the four decades before World War II, it became a regional industrial center and the population tripled, reaching 68,000 by 1939. Jews were important contributors to the city’s development, and comprised nearly 20% of residents. My family was among the migrants to the city during this time. By the end of the war, most of Włocławek’s Jews had been murdered, the synagogues burned, and the cemetery desecrated.

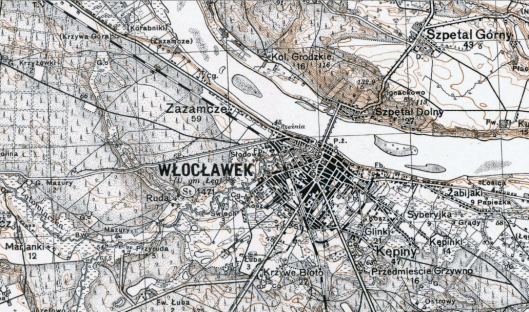

Map of Włocławek in 1930. Piwna Street is to the left of the bridge, just past an estuary opening out to the river. Map by Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny.

Piwna Street is located off of Wyszyński Street (one of the main routes through town). About one third of the way along its short length it makes a 90 degree turn and runs for another block parallel to the Vistula River. On the river side is a massive two story building and dock that includes the Rejs na Przystani Café. Across the street, colorful depictions of fruits and the products made with them decorate the wall around the Delecta factory (see the cover photo of the Facebook page above). Until the Forgotten Street project, nothing indicated that Piwna was called the “Street of Death” after the Nazi occupation.

In September of 1939, the city’s synagogues were burned to the ground and the Jewish population was terrorized (read more about this here); some were arrested while others were killed. The retreating Polish forces had blown up the bridge across the Vistula, so the Nazis decided to replace it with a pontoon bridge at Piwna Street. But first the riverbank had to be reinforced. Captive Jews were forced to do this backbreaking work, using the stone and concrete remnants of the synagogue as building materials. Many died in the process, hence the name “Street of Death.”

What’s extraordinary about the high schoolers’ project is how effectively it brings into the present an awareness of the past. It does so with a wide variety of archival information, photographs, and first-person recollections. The public nature of the fan page also meant that other people learned about this history and could even contribute to it. For instance, one viewer posted this gouache painting of Piwna Street from the mid-19th century.

The view across Zgłowiączki Estuary and Piwna Street. Gouache by Alfons Matuszkiewicz, c. 1853. Posted on Włocławkska Zapomniana Ulica

To date the fan page has 1773 “likes.” Another component of the project was the posting of a QR code that when scanned with a smartphone connects to a brief explanation of the history of Piwna Street in four languages. QR codes were also posted at several other sites around town that are associated with Jewish culture (listen here).

QR code linking to a brief history of Piwna Street.

For now, these notices are just on laminated paper, but the hope is that something more permanent will be installed so visitors will continue to connect here and then—this particular location with the events that occurred in the past. When I visited in June, the city’s president expressed his support for the project. The question remains where the money will come from to pay for a more lasting marker. Still, with people of good will and extraordinary energy like the teachers and students at the Automotive High School, I’m hopeful something will be done in the not too distant future.

The teachers who worked on the project Włocławska Zapomniana Ulica: from the left, Anita Kaniewska-Kwiatkowska, Monika Lamka-Czerwińska, and Robert Feter.

In Warsaw, the conference

In Warsaw, the conference