NOTE: This overview of my recent discoveries at the Polish Underground Movement Study Trust, Studium Polskiej Podziemniej (SPP) got so long I am publishing it in three separate posts. Here is part III. During the German occupation of Poland during World War II, the Polish Underground Army worked in secret to resist, sabotage, and fight against the Nazis. Another name for the Polish forces is “AK,” short for “Armia Krajowa,” or “Home Army.” I talk about the soldiers as “the partisans;” in Polish sources they are also called “konspiracja,” “the conspiracy.”

Sorry it’s taken a while for me to get to part III. The semester has begun which means I’ve been very busy.

Pencil sketch of Maria Bereday from the 1950s, signed Ditri. Friends tell me she looks like a spy.

All of the questions the archivist Krystyna asked me about the names Mama went by paid off because she found another file; the envelope was mislabeled “Maria Fijułkowska.” Inside was a six-page report, relacja, Mama had written titled, “Outline of Courier Work.”

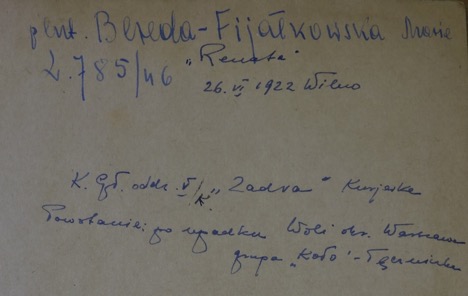

Initially, neither Krystyna nor I found this file because not only was “Bereda” missing, but Fijałkowska was also misspelled. Krystyna wrote “Fijałkowska” on a new envelope; I don’t know why she didn’t also add the Bereda, even after I pointed out that Mama’s full name was hand-written in large letters along the left margin of the document’s first page. Around World War II, the family usually used the name Bereda-Fijałkowska. Mama told me they added the Fijałkowski/a, which was grandpa Bereda’s mother’s maiden name and a name associated with the Polish gentry, because of Babcia’s social aspirations.

Mama’s name (Bereda-Fijałkowska) and pseudonym “Renata” in the margins of her typewritten report.

Mama’s report matches up with some of the stories she told me, and confirms some of what she did during the occupation. It also gives more details about the way her courier unit “Zadra,” was organized, and how couriers carried out their duties. The report is dry and factual. It contains no specifics about her emotional engagement or personal thoughts. A historian might find it interesting for what it reveals about the operations of the Underground conspiracy. I keep trying to look beyond the words to find the person behind them.

She writes, that “Zadra” started out very small, and because the work wasn’t systematized, the couriers were on call at all times. “By the end of 1942,” she writes, “the number of couriers stabilized at 15, and that group became close and experienced, and worked together for a long time without changing members.” This all changed in the fall of 1943 when the occupier, okupant, limited train travel to Germans only. Overnight, the courier corps dropped from 60 to just six who spoke German well and had German papers. “The work for these couriers during this time was nonstop,” she continues, “The number of trips for each courier came to 10-12 per month, depending on the route.” My mother doesn’t state it in the report, but she must have been one of the couriers who carried out missions during this time. Some of her most vivid stories were about traveling in the train cars with an assumed identity as a “volksdeutch,” a half-German whose father was fighting for the Reich on the Eastern front.

After about two months, the courier corps were reorganized and expanded, with more reserve couriers brought into regular service. In the half year before the Warsaw Uprising, the number of couriers in her unit approached 40, and overall reached 100.

The duties of the couriers included delivering coded and uncoded orders hidden in ordinary objects such as candles or paint, special messages that had to be handed to specific commanders, and large sums of money (1/4-12 million zloties in 500 zloty bills). Some missions involved carrying the messages brought by paratroopers they called “ptaszki,” “little birds.” This is the code name for the cichociemni, the officers who parachuted in from the West carrying money and messages from the Polish Government in Exile.

The report includes an example of a special mission Mama undertook at the end of 1943. Instead of being briefed by her usual commander “Wanda”, “Beata,” the head of communication with the west, did it. “Wanda” gave her a special coded message she had to hand directly to the chief of staff or the commander of the Radom District. This was to occur in private with no witnesses. Mama also had to memorize and deliver the oral message, “The commanders of the divisions and subdivisions of “Burza” require complete secrecy in the event of the invasion of the Russians.” Burza, Tempest, was the code name for the Warsaw Uprising.

Because the chief of staff wasn’t available on the day Mama arrived, she had to spend the night at a safe house. The next day, she delivered the messages to Chief of Staff “Rawicz” [his real name was Jan Stencel or Stenzel], but had to spend another two days before “Rawicz” returned from the forest, where the partisans were hiding out, with the required response for the Central Command in Warsaw.

Reading this sparked another memory for me. I think it was a big deal for Mama to stay away from home for so long, especially because her father didn’t know she was in the Underground. Her mother did know, though, and they hatched an alibi about a visit to Mama’s fiance’s family. Or maybe this is the story she told the authorities on the train to explain why she was returning several days late. Hopefully, my brothers remember this story, too, and can confirm one of these versions.

The documents from the Studium Polski Podziemnej in London have been a lynch pin that holds together information from a variety of sources. While I was there, I also found a citation for Communication, Sabotage, and Diversion: Women in the Home Army, Łączność, Sabotaż, Dywersja: Kobiety w Armii Krajowej, published in 1985. The book was written in Polish but published in London. I found a copy of it at an online used bookstore whose brick and mortar shop is in Warsaw. I called, and sure enough they had it in the shop, so I picked it up while I was in Warsaw. It contains the recollections of the head of the Women’s division of Central Command (VK) Janina Karasiówna, the oficer who confirmed Mama’s verification file. Another chapter contains the report of Natalia Żukowska who was the assistant commander of Mama’s courier unit; Mama identifies her by her pseudonym “Klara.” From Żukowska’s report, I learned that “Zadra” was the name used by the couriers who had been working with the unit for the longest, but in 1943 the name was changed to “Dworzec Zachodni.” Reviewing Mama’s documents, I see now that she identified her unit as Zadra-Dworzec Zachodni in one place. She underlined it, too. Until I read this book, I had thought Dworzec Zachodni, which means Western Station, referred to Zadra’s location, not an alternative cryptonym. And then there’s this: the names of the 15 couriers, including “Renata.” That’s Mama’s pseudonym; her last name is misidentified as “Brodzka” instead of “Bereda,” but Natalia writes, “Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to decrypt all of the last names” (p. 118).

Mama was proud of her service for her country, but she was also painfully aware of the cost of war. She called herself a pacifist and the war solidified her abhorrence of armed conflict. I remember her asking, “Are there times when fighting is necessary?” I could tell from her voice that she wanted to believe all conflicts can be resolved peaceably. But her experience had taught her otherwise.