Two of Babcia’s brothers sailed to America during the first decade of the 20th century. They both established bakeries in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and the younger brother Philip also made a small fortune in real estate. Philip never had any children of his own, but he became the patriarch of the family in the US. For many years, he maintained the family circle that met monthly, and helped to sponsor relatives who came from Poland. At first relatives came to work, often starting out in his bakery. Later, during and after World War II, efforts to bring relatives over from Europe became more urgent. He wanted to save their lives.

The older brother came first. He is listed as “Abram,” on the ship manifest, though some relatives called him Abraham and others used his middle name Jan (the Polish form of John). He arrived in New York on the SS Moltke on January 24, 1906, and was released into the custody of his uncle Samuel Jaretzky, who was probably related to him through his wife Bertha/Blima. There is some confusion whether Bertha’s maiden name was Kolski or Jaretzky. Bertha’s great grandson Bob has heard different stories about this—either the names were used interchangeably or one branch of the family changed their name. As if that weren’t complicated enough, In the US, the Jaretzkys dropped the Slavic ending and became the Jarets.

Bertha joined her husband in May 1907 with their three young children, Nathan, Paulina, and Ewa. Their fourth child, Sarah, was born in 1909.

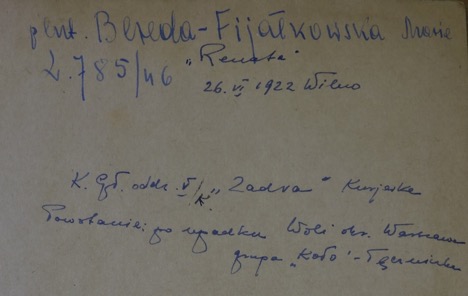

The Pifko brothers around 1908, New York. Front from left: Philip, Abraham, Paulina, Ewa, Bertha, Nathan. Back from left: Raphael Kolski, Sam and Max Alexander

The younger brother, Philip/Efraim arrived in December 1907. Philip was twenty-six and still a bachelor. At first, he lived with Abraham and worked as a driver of a bakery wagon. In 1910, Abraham was foreman at a pants manufacturer.

I love this photo of them.

Philip and Abraham Pifko in the US.

The photo was in my grandmother’s collection, inside the envelope she labeled “do not open,” along with the others in this post. I’m guessing it was taken in New York sometime in the 1910s. They seem to be inside, so maybe the automobile was just a prop of the photographer. I’ve tried to figure out what kind of car it is. It might be some sort of runabout from the earliest years of the 20th century.

Both brothers had dark hair, and usually wore a mustache without a beard. Abraham, as described by his sister Nunia, had “devil eyes;” he “liked girls and girls liked him.” She described Philip as “shy, pockmarked, and sweet.” Nunia described both as tall, but official documents list Philip’s height as 5’ 7”. He had grey eyes and a “light brown” complexion. That’s one reason I think Philip is on the left in this photo; he looks dark, like a gypsy. Also, I imagine Abraham, as the older brother, would have been in the driver’s seat. But then again, Philip was the bakery wagon driver so maybe I have it backwards.

The youngest sister, Malka/Maria c. 1912 in Poland

Nunia described the youngest sibling Maria/Malka as dark like a gypsy.

In 1911, Philip married Goldie Przedecka, though her name might have been Gertrude Jacobs. In my aunt’s tree, she is listed as the former, but their marriage record says the latter. Names are complicated in my family; Goldie’s sister and mother had the last name Jacobs or Posner. I’m still working on this.

Philip and Goldie never had any children, but his memory lives on, much more strongly than that of his brother. Abraham died at the age of 47 in 1925, and even though he had children and grandchildren, the cousins I have spoken with know very little about him. They have personal memories of his wife Bertha, who lived until 1968.

Census records show that by 1920, Philip had his own bakery. In 1930, his occupation is “employer.” In 1940, he is listed as a manager of real estate.

Philip’s legacy lives on thanks to everything he did for others during his lifetime. The census shows that he opened his home to a niece, sister-in-law, nephew, and mother-in-law. In 1925, his sister Sarah’s son Nathan Winawer, age 22, lived there, as well as Goldie’s much younger sister Sallie Jacobs, who was 21 years old. Around this time, Nathan and Sallie married. In 1930, Nathan and Sallie were no longer living with Philip, but Nathan was working in a bakery which may well have been Philip’s. In 1940, Bertha’s mother Nicha Posner and Abraham’s daughter Pauline lived with Philip and Goldie.

Other relatives also worked in Philip’s bakery, including Nathan’s brother Stanley Winawer. Stanley went on to open his own bakery, which he had for many years in Brooklyn. Philip helped family members in other ways. Joan, Philip’s grand niece, says he was involved in relatives’ schooling, and he was important for opening doors for them. She was just a child at the time, but she remembers anxious discussions about getting the family out of Poland during World War II.

I don’t have to look any further than my immediate family to see Philip’s generosity. When Babcia, my mother, and uncles came the US, Philip helped them, too. I’m not 100% sure whether they stayed with him, or just in an apartment he owned.

Bertha and Abraham Pifko in the US.

Philip may well have been following in his older brother’s footsteps. After all, Philip was one of several boarders at his brother’s in 1910. Others included the brother of Abraham’s wife, as well as two cousins, all of whom are in the photo from 1908 that’s at the top of this post. In the 1920 census, Abraham is listed as “proprietor” of a “bakerstore,” and a boarder named Charles Jacobs lived with them. Charles, age 35, had come from Poland in 1913 and worked as a bakery clerk. Could he be related to Philip’s wife Goldie, whose maiden name might also have been Jacobs?

I keep trying to fit the pieces together, to tell a story about their lives.