Our last two days in Żychlin highlight the importance of presence. If we hadn’t stayed here several days, we probably wouldn’t have learned everything we did. As we cleared more of the stubborn blackthorn bushes, the cemetery revealed more secrets. After seeing the progress we were making, the inhabitants of Żychlin opened up to us, too.

How would you respond if a group of foreigners come into your town and started weed whacking a cemetery? My guess is most of us would just watch from a distance, curious and a bit suspicious.

By Wednesday, people started telling us stories they pulled out of the depths of their memory. Others claimed ignorance about the town’s Jewish history, but the more we engaged in conversation, the clearer it was they knew more than they had initially let on.

ADJCP member David Goren, whose ancestors came from Żychlin, accompanied me to ask some of the neighbors about the cemetery. We collected important testimony that will help us bring Jewish memory back in this community.

The Wujcikowskis live across the street from the cemetery. They had already shown us kindness, letting all the volunteers use their bathroom. David had noticed historical photos in their flower shop suggesting they had lived there a long time. In fact, the large property and house have been in the family since before the war. When Katarzyna (Kasia) didn’t know the answers to our questions, she escorted us to her parents Henryka (Henia) and Grzegorz Wujcikowski who came out of the farm building next to the flower shop. They greeted us warmly. Though they weren’t sure they could help us find old photographs of the cemetery, Grzegorz shared his family history with us. The property originally belonged to Grzegorz’s father’s uncle. Because it was one of the finest houses in town, some of the occupying Gestapo moved in and fenced the land to raise horses. Grzegorz’s aunt and uncle weren’t forced to leave, instead sharing the three-story house with the Germans. After the war, Grzegorz’s parents joined their aunt and uncle, who had no children of their own, and eventually became the owners of the property.

Grzegorz was born after the war. He knew Moshe Zyslander, a Holocaust survivor from Żychlin who emigrated to Israel. In 1989, Zyslander led the initiative to build the memorial monuments in the Jewish cemetery, as well as the surrounding gate and fence. When the Wujcikowskis learned about Zyslander’s plans, they returned the tombstone fragments that the Germans had taken from the cemetery to build a pig sty, the same farm building where Grzegorz and Henia had been working when we arrived. The stones removed from its walls make up the bulk of the 50 tombstone fragments embedded in concrete mounds in the cemetery. Whenever Zyslander returned to visit the cemetery, he would stop by the Wujcikowski’s for a visit.

The Wujcikowskis showed kindness to Jewish descendants in the past and continue to do so today.

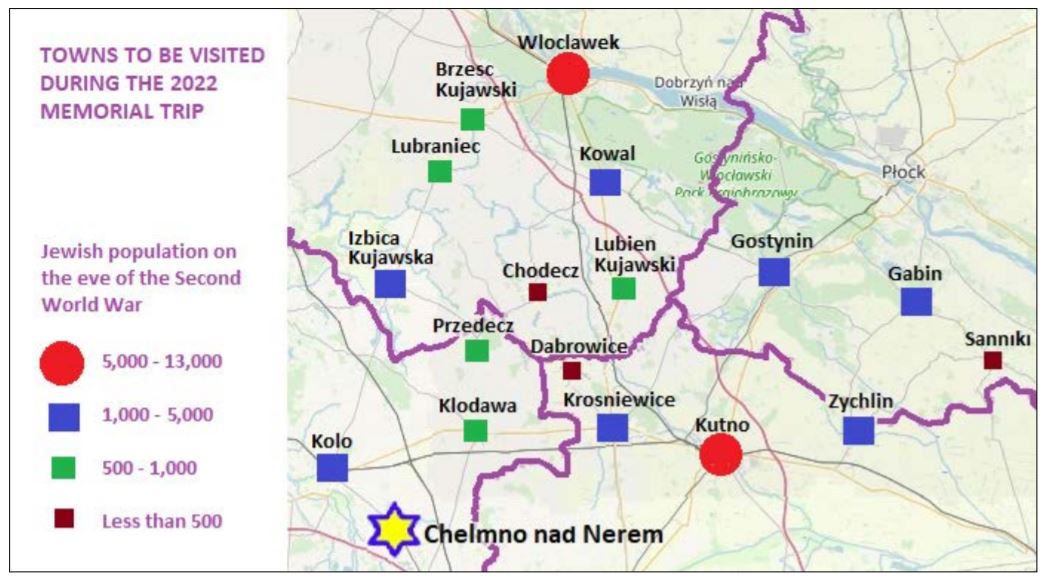

I’ve been very concerned about properly marking and memorializing the mass graves in the cemetery. Reports in the archive of the National Institute of Memory document the shooting of 200 people in 1942. Other sources indicate that when the ghetto was liquidated, the infirm were shot on the spot rather than being transported to the Chełmno death camp. For the site to be designated officially, it’s important to obtain testimony from witnesses. We were able to talk to two people who were not witnesses themselves but were told about the murders by a close relative who saw what happened.

We spoke with the neighbor next door to the cemetery the day before we started our work. She confirmed she knew we were coming; the city had informed her. She showed us where the city had dropped off a dumpster for the brush we cleared. A big goat was chained up outside the cemetery along the dirt drive leading from the road. “We put her there to eat the grass, so the drive is passable,” she explained.

Over the next two days, she and her son were in and out of their yard feeding their fowl, doing their farm work, and keeping a covert eye on us. As we cleaned up on our third day of work, David and I approached their fence to invite them to the memorial service we planned for the next afternoon. Mrs. Anna came over with her son Marcin and grandchildren Marceli and Lena. Anna has observed the comings and goings at the cemetery since she married over 40 years ago. Her husband, who grew up in the house, did so even longer, until his death in February.

Anna remembers how nice the cemetery looked when she first married. People used the space as a kind of commons; they walked their dogs or sunbathed, and her son played soccer with his friends. On holidays (the Catholic holidays like All Saint’s Day), the family would light a candle lantern at the monuments in remembrance of the dead.

As the cemetery became overgrown, people started going there to drink, play music, and get into other kinds of trouble. Anna’s husband would chase them out, threatening to call the police. She understands people sometimes want to get together and drink, but why destroy a cemetery? Why walk their dogs there? The last time she was at the Catholic cemetery where her husband is buried, people were walking their dog there, too. It isn’t right. She doesn’t understand why people would destroy monuments, either. Why? They should respect them. Although she sometimes contradicted herself, her overall orientation towards us and the cemetery was benevolent. It also suggests a growing recognition that the Jewish cemetery is a sacred space.

Then, Anna confided something that might help us get the mass grave demarcated: a personal account of the crime, albeit second-hand.

When her father was a young boy, about the age her 9-year-old grandson is now, he walked across the fields to see what was happening at the cemetery. He witnessed Jews being shot, their bodies falling into a trench. He was so frightened he peed in his pants and ran home to his mother.

Henryk Olszewski is a local amateur historian whom I have known for ten years. He had a stroke two years ago and has been slowly recovering. He manages the website and Facebook page Żychlin Historia with his wife Agnieszka. He has an unconventional way of presenting information and sometimes his posts perpetuate stereotypes about Jews and Polish-Jewish relations, but he’s a dogged researcher.

Agnieszka visited us at the cemetery with photos she and Henryk took in 2019 of a rusty sign; though the white lettering has faded, enough remains to make out “Wspólny Grób zamordowanych w czasie okupacji przez Hitlerowców” (“Collective Grave of those murdered during the Nazi occupation”). She, David, and I walked around the back of the cemetery, and after a few false turns, we found an entrance to a clearing where the back of the sign was visible. We also found some large boulders. Could they be fragments of a commemorative stone? We asked a few people why there are places in and around the cemetery that are less overgrown or even barren of vegetation. One possibility could be that the lye spread over mass graves made the soil infertile.

Thursday evening, Steven and I visited the Olszewskis at their home. While they treated us to pierogi, stuffed pancakes, and a plateful of tasty cakes, I asked Henryk to remind me the name of a man I met during my first visit to Żychlin. Of course he knew, and immediately picked up the phone to call Józef Kowalski so I could check on a story he told me. Józef confirmed that his grandfather, who was a young man during the occupation, was called out by the Gestapo one night and ordered to dig a ditch in the Jewish cemetery. His grandfather, his mother’s father, told him the story directly. Józef also confirmed the ditch was where the people shot in the cemetery were buried.

The dissonance between the social nature of our interactions and the horrific topics we discussed doesn’t escape me. And yet, these kinds of connections are what make possible the recovery of difficult memories. Our work goes beyond the restoration of the physical space of the cemetery, to something deeper. We’re also restoring the memory of the people who inhabited the city over 80 years ago, and the events that took them away forever.