Day two began with beautiful sunshine. The first for days, we were told.

We met our guide Tomasz where we left off yesterday, outside the POLIN Museum.

The Monument to the Ghetto Heroes was dedicated in 1948, 5 years after the ghetto uprising. The relief sculpture features a heroic central figure that Szymon compared to a socialist realist superhero. Most of the figures around him are young, as were most of the ghetto uprising fighters. Behind the central hero floats a woman with her breast exposed holding a baby, perhaps symbolic of Matka Polka–the idealized Polish mother, though perhaps also reminiscent of Madonna and the Christ child. The image emphasizes the heroism of the ghetto fighters. This is the best known side of the monument.

The relief on the back paints a different portrait of suffering and oppression. A line of robed figures tread heavily with down-turned faces. On this side, the central figure looks like a rabbi; he’s older with a flowing beard, holding a Torah scroll in his hand. The helmets and bayonets of Nazi soldiers hover above the line of hunched figures. Szymon pointed out the glittering black stone along the front of the platform, intended for a Nazi monument that never was built, and repurposed by survivors as a symbolic act of defiance.

We continued along the trail of the ghetto heroes, recognized on a series of metal cubes, then stopped at 18 Miła Street, where a dirt mound and monument mark the location of a bunker where ghetto heroes and civilians chose suicide rather than death at the hands of the occupiers.

These weren’t the only Jewish leaders who committed suicide. Judenrat leader Adam Czerniaków took his own life when he realized he couldn’t stop the final removals of ghetto residents to the death camps. Szmul Zygielbojm, a Jewish representative in the Polish government in exile, died by suicide after he learned the details of the murder of the Jewish people back in Poland. I wonder what my students think of this. It seems that for many Americans, suicide is an individual choice, not one motivated by a sense of collective grief or defiance. We aren’t facing down genocide, either…

We continued on to Umschlagplatz, where captives were gathered for transport to the camps.

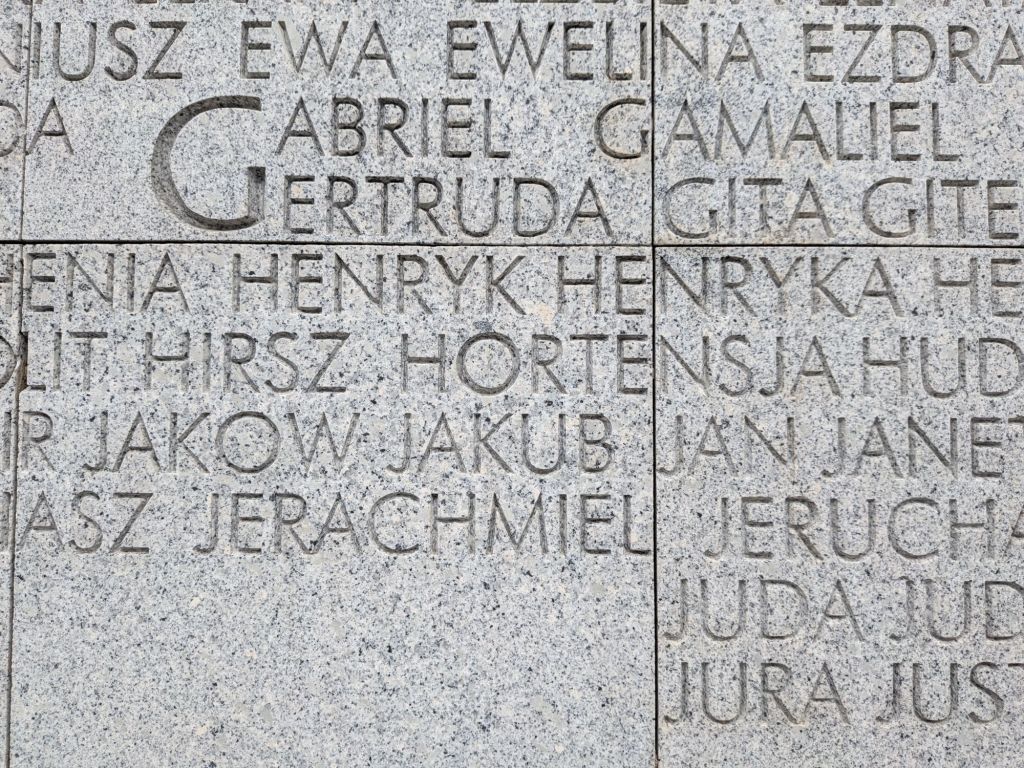

The walls inside are inscribed with the first names of victims. I took a photo of Jakub in memory of my grandfather Jakub Rotblit and my grandmother’s brother Jakub Piwko, both of whom died in 1942, likely victims of the Holocaust

We finished our tour at the Jewish Historical Institute, where many of the victims’ personal words are displayed along with one of the milk cans where Ringelblum hid the archive documenting life in the ghetto. Some of the saved documents are on display, including poetry, personal accounts, and official reports. One listing the number of victims in different towns says there were 3500 in Żychlin and 6500 in Kutno.

As we departed, thunder rumbled, the sky opened up and rain turned to hail.

“Is the weather always like this here?” a student asked. “No,” I replied. “That was really unusual.”