Presence matters. By spending time in the Żychlin Jewish cemetery, we’ve accumulated more knowledge about the town’s Jewish community and we’ve deepened connections with local inhabitants.

Toward the end of the day, a man living a few doors down from the cemetery stopped by to tell us he had found a tombstone in his garden about three years ago when he built a fence. He noticed from the lettering it came from the Jewish cemetery but didn’t know who to contact or how to return it. He just kept it leaning up against his new fence until he heard we are in town. With the help of a couple of volunteers, he brought it to us in his wheelbarrow and now it stands beside the one that was returned several days ago. People have told me that tombstones return once residents know that someone is taking care of the cemetery. Our presence here in Żychlin attests to that.

A candle lantern still burned in front of the first tombstone that returned, a reminder of the informal ceremony we had in the morning, lead by Żychlin descendant Lawrence Zlatkin. He told us about his connection to the town; something has drawn him back 5 or 6 times since he first came in 1985 with his father.

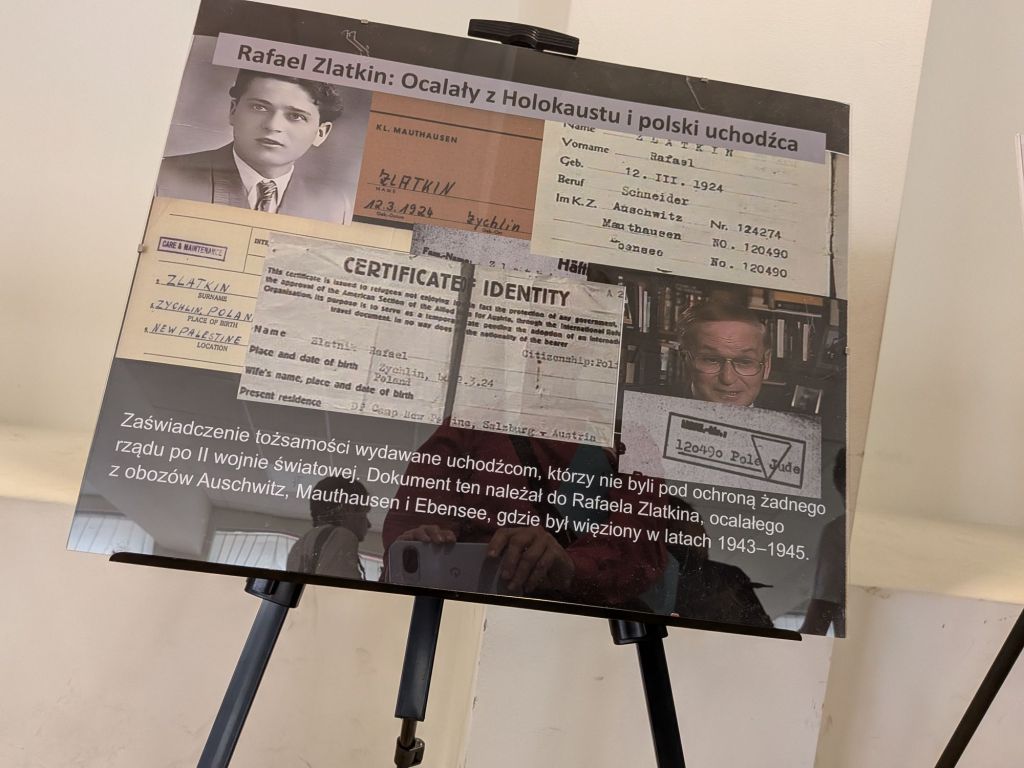

Raphael Zlatkin was born in Żychlin in 1924 and he was just a teenager when the war broke out. His younger brother was sent to a work camp, but he managed to avoid capture. He didn’t want to leave his mother all alone. Then, he was warned that staying was a death sentence so at the age of 17 he signed up for transport to a work camp. He spent two years in Auschwitz working in food procurement and making himself indispensable to his captors. He was able to smuggle food to his younger brother and others he knew from Żychlin, helping to keep them alive. In January 1945, as the Soviet troops were approaching Raphael elected not to stay, instead traveling west where he spent time in two other camps before he was finally liberated. From his modest beginnings in a basement apartment at 3 Narutowicza Street in Żychlin, he became a successful businessman in the US.

Lawrence said Kaddish in Hebrew and then in English, explaining it doesn’t say anything about the dead but it rather praises God and calls for peace. Everyone laid stones on the tombstone as a mark of remembrance for those who were buried in the cemetery.

In the afternoon we visited the Community Center where Henry Olszewski had an exhibition about the Jewish history of Żychlin, with photographs of the synagogue and biographic details about Jewish inhabitants including Raphael Zlatkin.

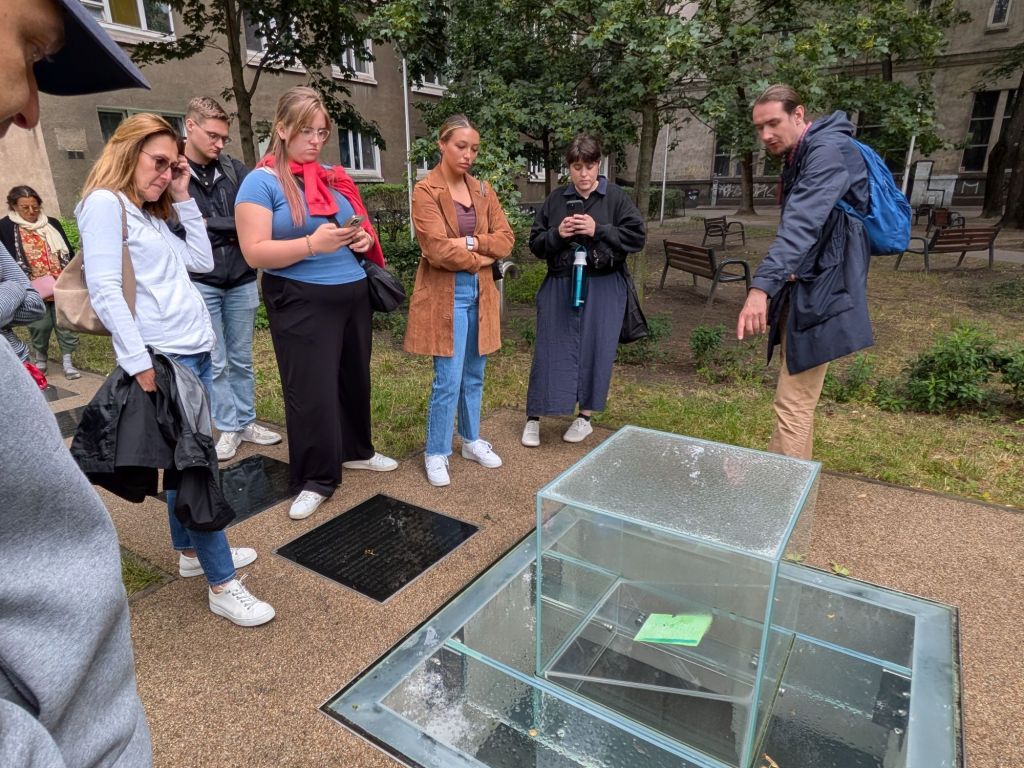

Not everyone could attend because they were hard at work helping UA Archaeology graduate student Claiborne Sea run the GPR (ground-penetrating radar) across the sites we had cleared. He showed the other students how the machine operates and gave them opportunities to operate the device. Claiborne’s work has only begun. It will take weeks to process the data and analyze the results.

More from UA archaeology graduate student Michele Hoferitza:

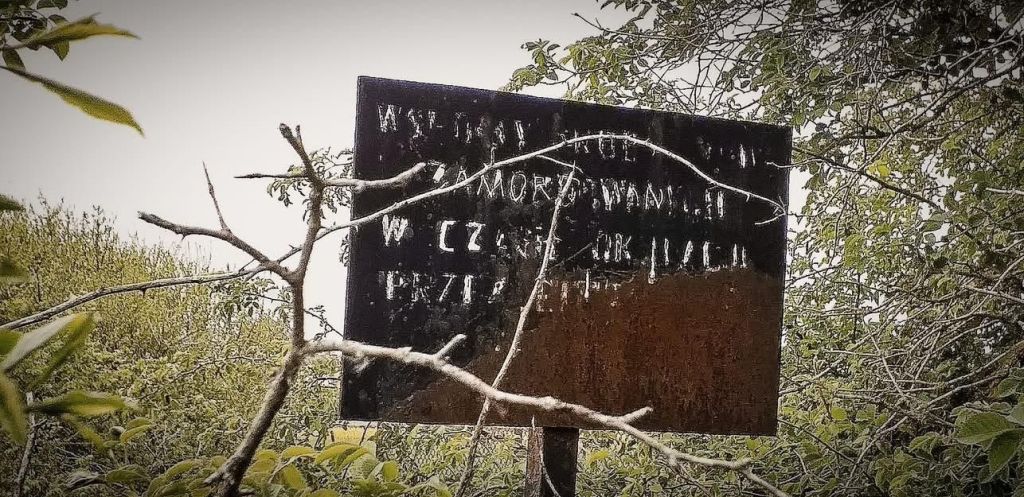

I figured I would post about our Europe trip a week at a time, but this week in Poland is going to need some extra explanation, and there are too many photos to dump. We are here as volunteers for the Matzevah Foundation, a US-based organization that works to preserve Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Many were simply obliterated by Nazis, and others were sites of mass execution before gas chambers were systematically used. Both are the case for our site in Zychlin, where LiDAR data has shown two depressed areas under dense growth of blackthorn. We have cleared a significant area in order to do a GPR survey to verify a mass burial site. It has been a lot of physical work, but it feels amazing to be part of this project. We are not just uncovering history, but living it. As we have worked, a few local people have brought old Jewish headstones they have found on farm property, recognizing that these monuments were taken to desecrate the memory of those who died. Restoring these is a sacred work of healing and remembrance.

From Steven Reece of the Matzevah Foundation:

While some volunteers continued to clear the overgrowth, the main activity was an introduction to the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) that was used to evaluate the mass grave within the cemetery. Students from the University of Alabama learned how to use the equipment and take some initial findings. The GPR investigators will need time to analyze the results so those will come at a later date.

We also held a commemorative ceremony where Lawrence Zlatkin said Kaddish. About 25 people joined us today including Grzegorz Ambroziak, the major of Żychlin.

Thank you to the many local volunteers who joined us again today…your efforts made a big difference in what we were able to accomplish!

From volunteer Michael Mooney:

On the final day in Żychlin, our team completed an incredibly meaningful day of volunteer work at the Jewish cemetery. While some of us cleared overgrowth, the main focus was introducing Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) technology to evaluate a suspected mass grave on site. Students from the University of Alabama learned to use the equipment and began initial surveys; the results will take time to analyze, but we hope they’ll shed more light on the tragic history of Żychlin’s Jewish community.

Throughout the day, we made several poignant discoveries—including human bones exposed above ground, among them the leg bones of a toddler—painful reminders of the atrocities endured here during the Holocaust. In a remarkable moment, a neighbor living four houses away approached and revealed he had a Jewish headstone in his garden, likely displaced when Nazis destroyed the cemetery. The stone, belonging to a 96-year-old woman named Beila, will now be returned to its rightful place, helping to reclaim her memory and dignity.

We also held a moving commemorative ceremony at the cemetery, with Lawrence Zlatkin reciting Kaddish in memory of those lost. Roughly 25 people attended, including Mayor Grzegorz Ambroziak and many local residents, whose dedication made all the difference.

At the end of the day, before leaving the cemetery, we gathered to respectfully bury the bones we found—ensuring those whose remains were uncovered received the dignity and rest they so deserve.

Our project is part of ongoing research led by Professor Marysia Galbraith of the University of Alabama—a descendant of Żychlin Jews—who documents these histories, stories, and testimonies of survivors and witnesses to ensure that the past is not forgotten.