Tags

11 Wednesday Jun 2025

Tags

19 Friday May 2023

Posted in Association of Descendants of Jewish Central Poland, Commemoration, Memory, Poland, Polish-Jewish Heritage, Polish-Jewish relations, Włocławek

≈ Comments Off on We’re From Here/Jesteśmy stąd: ADJCP memorial tour

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

02 Friday Dec 2022

Włocławek, September 12-16 and September 28

With a population of 107,000, Włocławek is the largest town in this part of central Poland, followed by Kutno which has 42,700 residents.

Włocławek will be the home base for the ADJCP memorial trip in May 2023. Roberta and I spent several days there to plan the trip and I returned a couple of weeks later to follow up on a few things. We reserved a block of rooms for the memorial trip in the Pałac Bursztynowy, a three-star hotel built to look like an old manor house, with an elaborate formal garden all around it. Roberta and I sampled the menu at the hotel restaurant. They have a good assortment of soups, salads, appetizers, and main courses, all tastefully prepared. The white asparagus soup with smoked salmon was particularly tasty. We also made arrangements with a bus company that will provide transportation during the memorial trip.

In Włocławek, we met with partners who agreed to help organize activities for us. Included among our partners are schoolteachers Anita Kaniewska-Kwiatkowska who teaches history at the Automotive High School, Robert Feter who teaches computer science at the same school, and Monika Lamka-Czerwińska who teaches at a school for children with disabilities. They have led several award-winning programs in which their students learned about and did research about the city’s Jewish community. See for example Włocławek Zapomniana Ulica, a Facebook page that was developed as part of one of these projects. Another outcome of this project is a sign posted on Piwna Street with a QR code linking to a recorded message outlining the wartime history of the Jewish population in this place.

On the morning of September 13, Roberta and I met students at the Automotive High School. We were escorted to the library, a room the size of a large classroom. Extra chairs filled all the space between the round tables. A reporter from the local paper came and took photos. Two students shot video for a class in television production with the plan to create a short program about our visit.

Students filed in one class at a time. In attendance were students studying psychology/pedagogy, computer science, and technical studies. This school also has classes for students with physical and mental disabilities.

Before we began, I spoke briefly with the first group that arrived, girls studying psychology and pedagogy. Their teacher Anita Kaniewska explained they will work with her on a project about Jewish history and culture and they will participate in our memorial trip. The room filled up. Over 80 students attended. We delivered our presentation in English and I’m surprised how well it went. A good number of the students understood, and those who didn’t know much English seemed attentive nevertheless.

Roberta and I took turns explaining our family connection to central Poland. Then we asked them what they knew about Jewish culture and religion, mostly as a way to fill in some details and point out similarities and differences to Polish culture and Christian faith. Finally, we invited them to ask us questions, which we answered. Their questions included:

Afterwards, one of the teachers said she was very pleased with the students’ level of engagement. Even one of their students who has autism asked a question. Five girls from Anita’s class thanked us and told us how moved they were by our stories and our presence. They asked if they could give us a hug. It was very sweet.

Photos from our visit were posted on the school website.

We had to hurry to our appointment with the mayor. Anita accompanied us. Marek Wojtkowski, whose official title is President of Wloclawek, expressed support for the ADJCP and efforts to memorialize the city’s Jewish history. He agreed to meet memorial trip participants and to welcome us to Włocławek.

Together with Anita, we proposed two projects: a Jewish history trail with signs and QR codes outlining events that occurred in particular places around the city; and a portable exhibition on retractable panels that can be moved and set up easily. President Wojtowski supports both these ideas. He agreed to help obtain permission to mount the historical trail signs on buildings.

President Wojtkowski noted his background as an historian, and said it is important that this history return, especially for young people.

Few traces remain of Włocławek’s Jewish community, which before the war numbered 20,000 people (20% of the city’s population). The two synagogues were burned down during the first days of the Nazi invasion on Rosh Hashana 1939. The cemetery was cleared of tombstones, and during the communist period a school was built on the site. In 2000, a group of descendants in collaboration with the city erected a memorial in front of the school in the shape of a matzevah. The text says in Polish and Hebrew “At this site Germans created a ghetto from which in 1942 they deported Polish citizens of Jewish origin to death camps.” Roberta and I lit candles for my relatives and all the others buried at this site.

Meeting with Mirka Stojak, September 28

When I returned to Włocławek on September 28, I met with Mirka Stojak, who for over 20 years has been meeting with and assisting Jewish descendants who have visited Włocławek. Mirka has documented the lives of Włocławek’s Jews in historical texts, prose, poetry, and on her webpage Żydzi Włocławek. Each year, she gives presentations at schools where she tells the stories of the city’s Jewish residents and reads her original poetry and stories. She has also worked with students on theatrical and musical productions on related themes. Longin Graczyk of the Ari Ari Foundation has worked with Anita and Mirka on other projects. Most recently, Mirka led a “Sentimental Walk” around historic Włocławek in which she told the stories of Jewish residents who used to live at various addresses. The Ari Ari Foundation and the local government where among the sponsors of the event. The ADJCP is listed as well!?!

Mirka will join Anita and Longin on the organizing committee for our memorial trip. She is also happy to prepare a presentation or to lead a walk for our visit, though she does not speak English so it will need to be translated.

Since retiring last year, Mirka has devoted even more time to writing. I bought her latest book Pamięci Włocłaswkich Żydów (In Memory of Włocławek Jews), a combination of history, stories, poems, and the memoir of Jakub Bukowski, who turns out to have been a neighbor of my cousins. Bukowski mentions Mirka Kolska, my mother’s first cousin, was one of classmates.

I visited the city museum to see the extraordinary exhibition of faience pottery. This industry was started and dominated by Jewish industrialists. Many of the woman who painted the floral designs were Polish. During the war, the industry was taken over by the Germans and then passed into Polish hands after the war. During communism, the factories became the property of the national government. The last factories closed right around the time communism fell. They were unable to reorganize within the emerging capitalist economy.

I hope we include the exhibition in our memorial trip.

07 Monday Dec 2020

Posted in Kutno, World War II, Włocławek, Żychlin

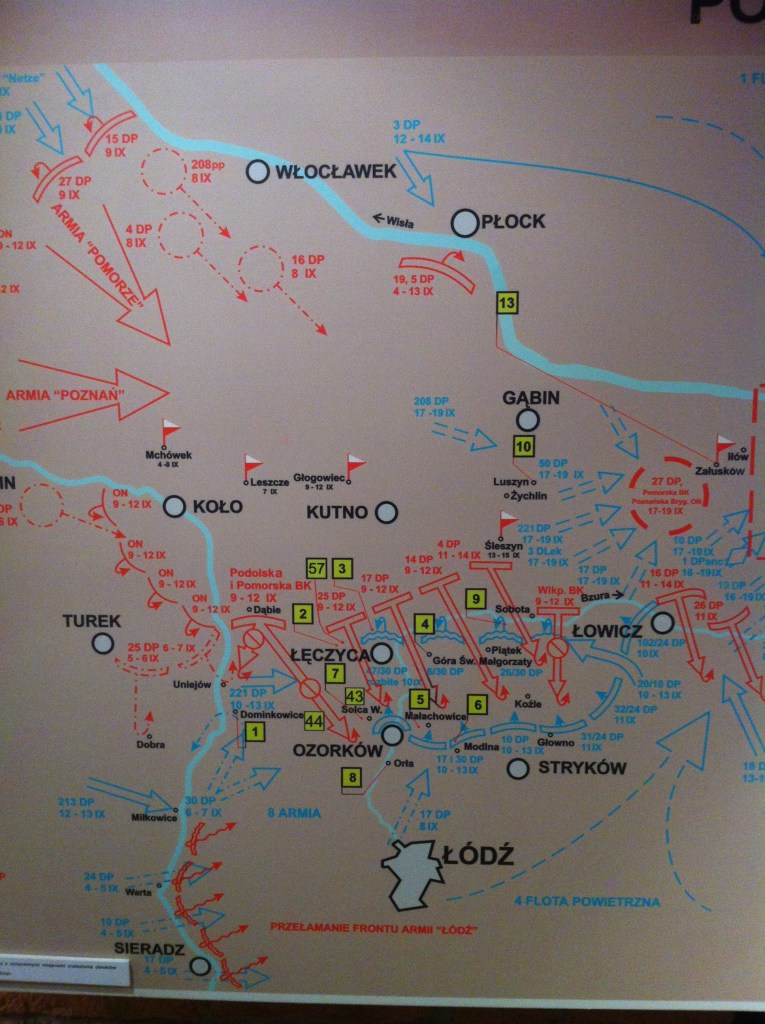

While going through photos, I came across this map from the Muzeum Uzbrojenia in Poznan showing the movement of the Polish army (shown in red) through central Poland when the Nazis invaded in September 1939 :

It’s a little hard for me to read, but I believe Poland had a stronghold in the Kutno region and for a few days they held back the Nazis (shown in blue).

This region is exactly where my family came from. My great grandmother was born in Żychlin and eventually settled with her husband and children in Włocławek. They would have been long gone when the war started, but some of my grandmother’s siblings were still living in Włocławek. Here’s another layer of memory I need to integrate into my family story. How profoundly destabilizing it must have been for them to watch as the Polish forces fell and they became foreigners in their own country.

06 Wednesday May 2020

Posted in Brześć Kujawski, Heritage work, Kutno, Nazi Camps, Polish-Jewish Heritage, World War II, Włocławek, Żychlin

It turns out I’m not the only one who dreams of doing Jewish heritage work in the land of my ancestors. The Association of Descendants of Jewish Central Poland has just gained nonprofit status and welcomes members.

It started at the initiative of Leon Zamosc, who reached out to others on JewishGen seeking information about ancestors from the region around Kutno and Włocławek. As the message from the founders explains:

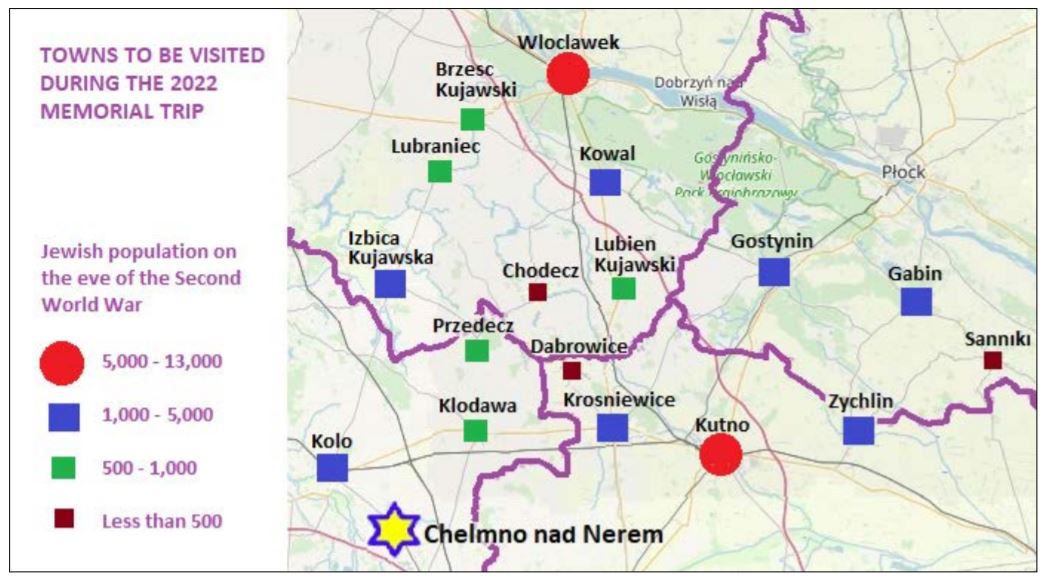

The concept of a regional organization of descendants developed out of an initiative to visit the districts of Wloclawek, Gostynin, and Kutno in order to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the destruction of the region’s Jewish communities during the Shoah. About 60 JewishGen researchers responded to the initial invitation, including 16 who volunteered as consultants for the planning of the Spring 2022 trip. In those early exchanges, some participants proposed the creation of a more permanent organization that would allow us to develop other activities related to the cultural heritage of the region’s shtetls. After studying the options, a subcommittee of 9 participants suggested ideas for possible activities and recommended the establishment of the ADJCP – Association of Descendants of Jewish Central Poland.

On the 2022 trip, we’ll participate in memorial activities at the Chełmno Death Camp. We will also learn about the history and culture of Jewish residents of the region, spending time in the larger cities of Włocławek, Kutno, and Gostynin. In additon, participants will have the opportunity to participate in small group excursions to the smaller cities and towns where their ancestors lived. We hope to contribute to a heritage project while we are there.

04 Monday May 2020

Posted in Bereda, Family, Genealogy, Identity, Israel, Kolski, Photographs, Polish-Jewish relations, Post-World War II, Pre-World War II, Warsaw, World War II, Włocławek

Now, the English-language MyHeritage blog has a story about us: Hidden Photo Reveals a Secret Past and Reunites a Family, written by Talya Ladell.

The article also contains cool colorized photos. You can compare the black and white originals with the color copies by dragging the cursor over the image.

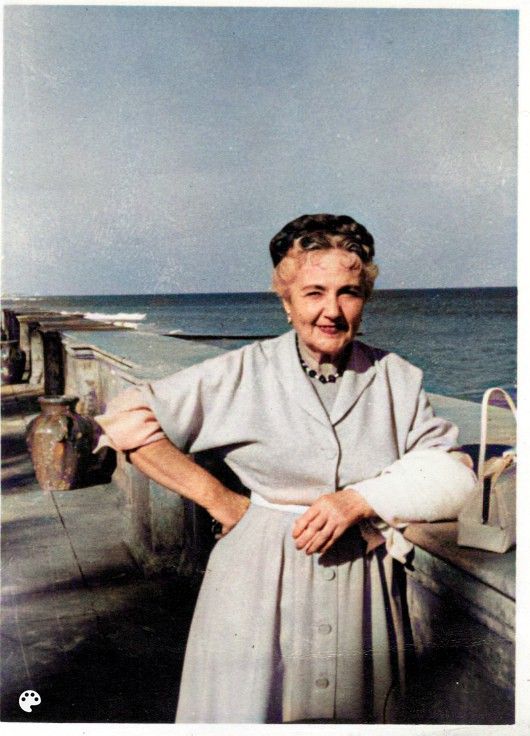

Babcia Halina in Florida during the 1950s. Colorized photo

23 Thursday Apr 2020

Posted in Bereda, Family, Genealogy, Israel, Kolski, Photographs, Polish-Jewish relations, Post-World War II, Pre-World War II, Survival, Trauma, Warsaw, World War II, Włocławek

I met my cousin Pini Doron in 2013 when I found his family tree online and wrote to ask if we might be related. He asked for proof, so I sent him the photo in the header of this blog, which he recognized from his own copy. He wrote back “welcome to the family” and ever since I have felt embraced by my extended family in Israel, with Pini at the heart of it. The photo, which includes both of our grandmothers, confirmed that we are cousins.

Last week, we were contacted by Nitay Elboym, who writes for the MyHeritage Hebrew-language blog. He decided to write about our family in commemoration of Holocaust Remembrance Day. It’s a story of connections and separations that span a century.

You can find it in Hebrew at the Internet news service YNet:

and in the MyHeritage blog:

Colorized photo of the family from about 1916. Marysia’s grandmother is sitting on the left and Pini’s grandmother is standing on the right

Thanks to a photo and a family tree: a Holocaust survivor son has found family members who disappeared

By Nitay Elboym

April 21, 2020

74-year-old Pini Doron of Hod Hasharon is a longtime MyHeritage user who built a family tree for many years dating back to 1800. Pini thought he had already finished his search, when he received a message with an old family picture. This time, he realized immediately, it was an extraordinary discovery.

“I get a lot of inquiries from people who think they’re related to me,” Pini says. “I am usually skeptical of my relation to them, so I politely ask everyone to explain how we are connected. In this case too, when I received the message, I responded that I would love to know what our family relationship is,” he recalls.

“Actually, at that time, I was pretty much at the beginning of my family history research,” recalls Marysia Galbraith, a professor of anthropology at the University of Alabama, USA. “I was looking for bits of information wherever possible. But when I saw Pini’s family tree on MyHeritage, I knew it was about me, I just didn’t know how. In short, I had no idea how to prove to him how I was related to his family tree, so I just sent the only picture I had. Besides my grandmother, I didn’t know who the people were. Then he answered me ‘Welcome to family.’ His reply almost made me cry. ”

The Piwko family lived in the town of Wloclawek, Poland. At the outbreak of World War II, Pini’s grandparents – Pinchas Kolski and his wife Rachel (nee Piwko) – and their two children, Mirka and Samek, were left there while Pini’s father was saved because he and his two brothers were sent to Israel before the war to work the family lands in Kfar Ata. “Because their city of residence was close to Warsaw, they were transferred to the Warsaw ghetto right at the beginning of the war, around 1940,” Pini says. “In the ghetto, Samek was murdered, and my grandfather died of illness. So my grandmother and her daughter Mirka were left alone, looking for a way to survive.”

Mirka and Rachel Kolski at Pinchas Kolski’s grave in the Warsaw Ghetto

Meanwhile, Rachel’s sister, Halina, lived in relative safety outside the Warsaw ghetto, because after divorcing her first Jewish husband, she remarried a Christian man named Zygmunt Bereda. “Rachel and Halina’s father were not ready to hear about this relationship. So, when she married a Christian, he sat shiva on her,” said Pini. “Her sisters tried from time to time to keep in touch, but because of their father, the connection got weaker.” Halina and Rachel’s father, who passed away around 1930, could not have imagined that it was precisely the person who, because of his religious identity, he rejected, would save not only his daughters, but also his other descendants.

When Halina told Zygmunt that her sister was in the ghetto alone with her daughter, he decided to come to their aid despite the risk involved. “Zygmunt was a very successful businessman with a lot of property. In addition, he probably had many connections, which opened doors to him that were closed to others,” explains Marysia. “He used these connections to forge documents for Rachel and her sister, which allowed them to escape the ghetto.”

Halina Bereda, Marysia’s grandmother. She and her Christian husband saved the family

Zygmunt Bereda. A Polish Christian who saved the family of his Jewish wife

But the matter did not end here. Zygmunt and Halina protected the two after they left the ghetto and hid them in buildings they owned throughout the war. At the same time, they were able to forge additional documents that allowed them to leave Poland to Switzerland, and from there, in 1949, the two immigrated to Israel.

“Years of disconnection ended thanks to a surviving photo and family tree on the MyHeritage website. Ever since we started chatting, I have found that Marysia isn’t only a wonderful person, she is also a thoughtful researcher,” says Pini. “She has set up a blog where she writes personally and collects her interesting findings. Everything she does is well organized, backed up by documents, and she knows how to find almost everything. She even studied Polish, which probably helps her a lot in genealogical research.”

At the end of the war, Warsaw was devastated by the bombings. The many businesses and houses that Zygmunt owned were also destroyed. He and Halina lost their property and had no place to live. The rescuers now needed help, and the one who came to their aid was the former wife of Samek, Rachel’s son who died in the Holocaust. After the war Halina and her daughter Maria, Marysia’s mother, immigrated to the United States and settled there.

“The truth was kept from us,” says Marysia, who has grown up as a Christian all her life. “For years, family members have been whispering about being Jewish, but never really getting into it. I have spent a long time trying to figure out why my mother and grandmother hid their Jewish heritage and why they were not in contact with Rachel. I think the trauma of the Holocaust left a deep scar on my grandmother. She thought, “If they don’t know, then it won’t hurt them.” That’s probably why they didn’t keep in touch with Rachel and her descendants in Israel.”

Since the family tree has linked Pini to Marysia the two speak regularly, and they have also met in Israel and in Poland with other family members. “When we went to the graves of our families, the sight was unusual. On one side of the cemetery wall are Jews with a rabbi, and on the other side are Christians with a priest,” Pini recalls. “But what is important? In the end, we are human beings and destiny connected us together.”

During the roots journey to Poland. Pini stands to the left and beside him Marysia

Pini’s Tree showing the family connection between Pini and Marysia

The image that led to the discovery – now in color

To revive the old image that made the exciting discovery, the company’s investigators used the MyHeritage In Color ™ auto-coloring tool and sent the result to Pini and Marysia. “It’s wonderful,” says Marysia. “I’m going to share the colorized picture with my family, including my 90-year-old aunt who will be especially happy.”

Colorized photo of the family from about 1916

20 Tuesday Mar 2018

Were Jews included as part of the Polish nation or were they excluded from it? This was one of my driving questions when I started to uncover the Jewish roots of my (Polish) mother’s family. I wondered if I might find my ancestors in some kind of hybrid Polish-Jewish space in which they identified as both Polish and Jewish. Or perhaps they lived in a world that ran parallel to that of their non-Jewish neighbors, with limited points of interaction. What I have found so far is neither straightforward nor consistent. It doesn’t fit entirely nor unambiguously into a narrative of hostile separation nor of peaceful coexistence. I’ll be focusing here on my ancestors’ lives before World War II. The Holocaust was such a devastating event that it needs to considered in its own terms, something I’ll try to do in another post.

The Polish lands were hospitable to my Jewish ancestors, allowing them to prosper for generations. My grandfather Jacob Rotblit owned a Ford dealership in the 1930s, and before then he was a manager of an international trading firm. Or maybe he sold jewelry. It’s hard to find absolute proof, but either way, he maintained important business interests.

Poland was under Russian, Prussian, and Austrian rule from the end of the 18th century until World War I. The region around Warsaw, where my family lived, was under Russian rule, though it had some degree of autonomy for some of this time. Map source and more information about the partitions of Poland: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/466910/Partitions-of-Poland

My grandmother’s father Hil Majer Piwko was in the lumber trade. Documents from the National Archive in Włocławek show he owned a building supply store in the 1920s, and according to Aunt Pat, he owned a sawmill before then. Pat also writes that he was recognized as an “honorary citizen of the Russian Empire” for his service during a cholera epidemic. This was sometime before 1918, when the region near Warsaw was part of the Russian Empire. Apparently, the title “honorary citizen” came with some of the rights that were normally reserved for the nobility.

So there was separation but also opportunity. It was not very easy for Jews to become gentry, unless perhaps through marriage, but there were other means by which they were granted special honors and rights. By comparison, different social classes faced road blocks against entering the gentry, regardless of ethnicity or religion. For instance, most peasants lacked the financial means and cultural capital to gain such social standing. At least in some times and places, wealthy, educated Jews would have had more avenues to social advancement.

More about my family’s prosperity can be read from the family portrait that was taken around 1916. Hil Majer and his wife Hinda had many children. They were wealthy enough to dress in fine fabrics. Hil Majer’s traditional clothing suggests that he had the freedom to practice his faith and customs, while his children were free to assimilate, as indicated by their modern clothing. Separation wasn’t just enforced by the majority, but also sometimes chosen to preserve cultural and religious distinctiveness.

The Piwkos c. 1916. For more about this photo see: The Photo That Started it All, Some Reassembled Stories, and What Year Was It?

Why did the family move from Hil Majer’s native Skierniewice to the village of Sobota, before settling down in Brześć Kujawski and then Włocławek? It seems likely they were following economic opportunities, but also possibly they were seeking a place more hospitable to Jews. This fits a common narrative about the Jews as wanderers. They arrived in Eastern Europe as tradespeople, financial advisers, and estate managers, and eventually established settled communities. But I’ve also been told that by the 19th century, most Jewish families stayed put. That’s why knowing the place of origin of one relative usually leads to many more relations.

Włocławek hadn’t always welcomed Jews. Until the end of the 18th century, it was a Church town, home to a bishop’s cathedral, with restrictions against Jewish residents. But then the city secularized, and as it industrialized and became an engine of commerce, the Jewish population also grew. Located as it was between Warsaw and the Baltic Coast on the Vistula River, Włocławek became an important port, and home to paper, ceramic, metal, chemical, and food processing factories.

Włocławek before 1898. Note the factories near the river. By Bolesław Julian Sztejner (1861-1921) (http://www.wuja.republika.pl/widoki_ogolne_wl.html) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In addition to economics and religion, political factors shaped the degree of inclusion available to Jews within the broader society. Antisemitism grew in the 1880s throughout the Polish lands, as Polish nationalists became more active in their pursuit of national sovereignty. Once Poland gained its autonomy in 1918, tensions deepened. Some political forces, led by Józef Piłsudski, argued for a broad definition of citizenship within the new Polish state, insuring equal rights for the 1/3 of the population that was Ukrainian, German, Jewish, and other minorities. Another political faction, led by Roman Dmowski, advocated for a narrower definition of Polishness, based on an idea of “pure blood,” by which he meant shared descent that also tied the nation to Catholicism. At the same time, Jewish nationalism grew, and took on a number of forms, leading some to embrace Yiddish culture, and others to espouse Zionism. Some Jewish nationalists dreamed of a safe place within the countries in which they lived, while others turned their eyes toward Palestine.

Włocławek became a crossroad for different varieties of Judaism, including Zionism, Hasidism, and Reform. Around the time that my great grandfather moved there, a new rabbi, Jehuda Lejb Kowalski, also arrived. He was very popular, and succeeded in reconciling the factions within the Jewish community. In 1902, Kowalski helped found the Mizrahi Party, and was a key leader in this Orthodox Zionist organization. Perhaps Kowalski is what drew the family to Włocławek? I’m not sure of Hil Majer’s affiliation, but his son-in-law, Rachel’s husband Pinkas, was a member of the Mizrahi Party in Włocławek, and a representative of the governing board of the city’s Jewish Community in 1931. Hil Majer’s oldest son Jacob represented the Zionist Party on the governing board from 1917 until 1922, and he was on the City Council from 1917-19. In other words, Jacob wasn’t only involved in Jewish political life; he also held a position in city government.

So there were opportunities to integrate into the broader society, to pursue economic and political goals, and to flourish as a distinct religious and cultural group.

But clearly there were problems that caused my relatives to leave for other countries, long before the German occupation and Nazi assaults against Jews. One of Hil Majer’s brothers went to Canada in the 1880s; the son of another went to Switzerland. In 1906-7, two of Hil Majer’s sons went to New York. Over the years, Philip sponsored many of the next generation who started out in the US at his bakery. Four more sisters, including my grandmother, also came to the US. Jacob’s children, as well as Rachel and her children, went to Palestine starting in the 1930s. Still, choosing, or even being forced, to leave didn’t necessarily signal a lack of attachment to Poland. For over a century, there have been mass migrations from the Polish lands by Catholics, Protestants, and Jews who, regardless of their national or ethnic affiliation, chased after their dreams in distant lands.

29 Monday Jan 2018

Posted in Cemeteries, Commemoration, Jewish Ghetto, Memory, Polish-Jewish relations, Włocławek

Thanks to Mirosława Stojak for all the work she does to preserve the memory of Jewish history and culture in Włocławek.

Here is a video from Holocaust Remembrance Day (January 27) when she and students and teachers from the Automotive High School visited the memorial at the site of the World War II Jewish ghetto, also the prewar Jewish cemetery.

Flim credit: Q4.pl, http://q4.pl/?id=17&news=170583

The interviews are in Polish, but even if you can’t understand the words, you can see that these people remember the Jewish history of their city. And they are passing on those memories to the next generation. They lit candle lanterns in front of the commemorative monument, and the students placed pebbles upon which they had written words like “traditions,” “love,” and “memories.”

There’s more about Włocławek’s Jews on Ms. Stojak’s website Zydzi.Wloclawek.pl. The tagline of her site: “Ku pamięci, z nadzieją, na pojednanie,” “In memory, with hope, for reconciliation.”

22 Friday Dec 2017

Posted in Family, Genealogy, Jewish immigrants, Kolski, Memory, Photographs, Piwko, Włocławek

This blog started with a photograph. A family portrait of adult siblings with their parents. The photo also instigated my search for my hidden Jewish ancestors.

The Photo that started it all

Here, in my great grandfather’s long beard, head covering, and black robe, I saw for the first time visible proof that I descend from Jews. It took a long time, but I managed to identify everyone in the photo, including my grandmother (Babcia) who appears in the bottom left, her hand resting proprietarily on her mother’s wrist.

Based on their clothing and ages, I have guessed this photo was taken sometime around World War I. But I just came across some new information about my grand uncle Philip, the man standing to the right, that throws this date into question. Let me walk through what I have figured out.

Two Pifko brothers came to America, Abraham in 1906 and Philip in 1907. Here they are with Abraham’s wife and children and some other relatives:

The Pifko brothers around 1908, New York. Front from left: Philip, Abraham, Paulina, Ewa, Bertha, Nathan. Back from left: Raphael Kolski, Sam and Max Alexander

This photo is easy to date; everything fits together. It must have been taken after Bertha and the children arrived in New York in May 1907, and Philip arrived in December 1907, but before Abraham and Bertha had their fourth child in October 1909. The style of Bertha’s dress is also consistent with this time period. Census records add another piece of supporting evidence; in 1910, all the people in the photo lived in the same household in Manhattan. So the photo was taken sometime between 1908 and the middle of 1909.

Philip and Abraham Pifko in the US.

In another photo of Philip and Abraham (on the right), they look a bit older, and Philip has grown a mustache. In my last post, I said that Philip is on the left, but my cousin Joan, who knew Philip when he was older, says she’s pretty sure he is on the right, driving the car. She also has no idea why his complexion was labeled “light brown” on an official document I found. His skin was not dark.

The photo that started this blog, and my search for ancestors, would seem to have been taken next, sometime around 1914-1918. Except it seems strange that Philip visited Poland during World War I.

Then, while looking through Philip’s documents on Ancestry.com, I clicked on a passport application from 1920. It was for both him and his wife Goldie, to go to England and France. According to what is written, Philip became a US citizen in January 1916, and resided in the US uninterruptedly since arriving in 1907. In response to a question about where he has lived outside of the US since his naturalization, the space is stamped, “I have never resided outside of the U.S.” Below, in response to a question about previous passports, it’s stamped “I have never had a passport.”

So this got me wondering. If Philip didn’t leave the country between 1907 and 1920, could the photo have been made later than I thought, in 1920? Could it have been when he traveled on this passport?

Goldie and Philip Pifko 1920, passport application photo

I found this passport application a while ago, but it didn’t occur to me until now that it might have a back. Sure enough, when I clicked to the next page in the database, there it was. The back of the form includes a place where a lawyer verified the truth of everything on it. There is also a handwritten note, “Applicant says he will not go to Russia or Poland. Instruct Amer consul [American Consulate] at France and England.” And even more convincingly, Philip and Goldie’s photo is attached at the bottom.

At age 37, Philip clearly seems older than in any of the other photos. His hair is receding (and, by the way, his skin does not look particularly dark).

It seems unlikely, after all, that the photo was taken in 1920. Could it have been taken before Philip’s departure in 1907? I went back to the photo itself, to reconsider all the details. First, I checked everyone’s ages. In 1907, my grandmother would have only been 13, but clearly she is older in the photo. The boy in front, sitting between his grandparents is Nathan Kolski, whose mother Regina died when he was born; several of my cousins have confirmed his identity. But Nathan was born in 1905, and he is definitely not a toddler in the photo. He almost certainly isn’t 15 either, making it unlikely the photo was taken in 1920. Also, the oldest sister Liba was 20 years older than Babcia. It’s really hard to tell for sure, but I would say that none of the women who are standing in the photo look as old as 48. Perhaps a couple are around 40. So again, considering everyone’s ages, it seems most likely the photo was taken around 1915, when Babcia was 21, Nathan was 10, Liba was 42, and Philip was 32.

It is also worth noting that the youngest child in the family, Malka, is missing, making me think the photo was taken after she died in 1913. Otherwise she would have been in it.

Next, I looked at the way everyone is dressed. Clearly, there is a great deal of variation between my great grandmother’s conservative dress and my grandmother’s short hemline and high heels. The dresses of the younger women flow; they are not fitted and buttoned up like Bertha’s in the photo from 1908. Fashion catalogs from the period show that during World War I, fashions changed markedly. Hemlines went up, waistlines became higher, and clothes used less fabric to conserve resources for the war. Other characteristics from the period include the “V” neckline with a lace inset, as well as attractive high heeled shoes, like Babcia and her sisters wear. The clothes date this photo back at my original estimate, 1914-1918.

I even considered whether I could be mistaken about the identity of the man standing to the right. Could it be the spouse of one of the sisters beside him? But several relatives have identified him as Philip, and he looks like Philip based on the other photos. Rachel’s husband Pinkus Kolski looked completely different. I don’t have a photo of Nunia’s husband, so I can’t compare.

But if the photo was taken around 1914-1918, how can Philip have been there? Occam’s razor says when there are multiple explanations, the simplest is probably the best one. The simplest explanation in this case is that Philip was indeed in Poland at some point during World War I. Maybe the photo was taken in celebration of his visit. Maybe a space was left between Jacob and Nunia to symbolically mark where Abraham, the brother who stayed in the US, would have stood. Maybe it was taken for Abraham, so he would have a memento of his kin back in Poland. That would explain why the photo was passed down in Abraham’s family. Many years later, his grandson made copies for my grandmother and other branches of the family.

Does that mean Philip lied on his passport application? Maybe not. If he traveled to Poland before he became a US citizen in 1916, maybe he didn’t need to report it on the form. And if that’s what happened, maybe I can pinpoint the photo more specifically to 1914-1916, before his hair had receded quite so much, and before the US entered the war. That seems like the simplest solution, even though it still doesn’t explain why Philip went back to Europe in the middle of a war.