A Guest Post by Michael Mooney of the Matzevah Foundation

Day two has wrapped up for the Matzevah Foundation, our core team of volunteers, three individuals from a local reintegration program, and several local residents who stepped forward to lend their hands. These community members have their own reasons for joining us—personal, deeply-felt convictions about the importance of this work. They rarely say much about it, but their quiet presence speaks volumes. Their support adds a layer of silent solidarity that is deeply moving.

Our main task today focused on continuing the physically intensive work of clearing the brush and thick overgrowth from the depressed area believed to mark the site of a mass grave—just outside Żychlin. The sunken terrain could be the final resting place of hundreds of Jews—families and children—who were massacred during the German occupation of Poland. Step by step, we’re reclaiming this space from years of neglect, trying to bring dignity to a site long obscured both by vegetation and silence. Evidence and testimonies collected over the years suggest this area may be one of many unmarked mass graves, now hidden within the landscape yet never truly forgotten.

Before the war, Żychlin was home to a thriving Jewish community, with Jews making up over 40% of the town’s population. They had their own schools, synagogues, businesses, and institutions woven into the daily life of the town. The Nazi invasion brought devastation—ghettoization, mass deportations, executions, and widespread destruction. Few Jews from Żychlin survived the war.

Later in the day, our group visited what remains of the town’s historic Jewish quarter. Only the gutted walls of a 19th-century synagogue still stand—silent and broken. The cheder (Jewish school) and mikveh (ritual bath) that once operated nearby were destroyed long ago. The courtyard is cracked pavement, overrun with weeds and scattered debris. There is no plaque. No sign. Just the vacant presence of what was once central to community life.

As we surveyed the site, a few residents peered from behind curtains or doorways, then disappeared back inside. One person reportedly remarked to a member of our team that the synagogue “should just be torn down.” Is this concern about safety and dereliction? Or is it also a quiet wish to erase uncomfortable history—to bury the memory of a tragically obliterated community? Is forgetting easier than remembering?

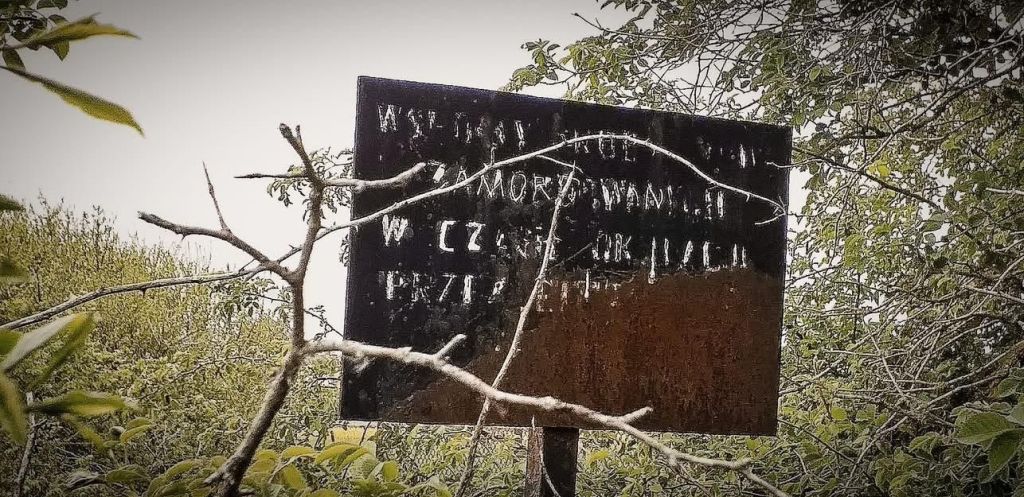

Near the clearing at the suspected grave site, we stumbled upon a weathered old sign—almost completely obscured by plants and exposure to the elements. The sign matches a photograph taken about eight years ago at (or near) this same location that once surfaced online. Most of the paint has worn away, but a few phrases remain legible:

– **”WSPÓLNY GRÓB”** – “In this place rest”

– **”ZAMORDOWANYCH”** – “Murdered people”

– **”W CZASIE OKUPACJI PRZEZ”** – “During the occupation by”

– One barely visible word at the bottom: **”HITLEROWCÓW,”** meaning “Nazis”

This style of memorial wording is common on World War II-era markers around Poland. It typically refers to civilians—often Jews or resistance members—murdered by the Nazis and buried in unmarked sites like this one.

Even in its deteriorated state, that plaque whispers a truth: this place is hallowed ground. And while some might look away, we cannot. Our work is about remembrance, dignity, and bearing witness to what many would rather forget.

When I return home, I plan to read *Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland* by Jan T. Gross. The book tells the horrifying account of how, in 1941, the Jews of Jedwabne were not killed by distant Nazis, but by their own non-Jewish neighbors in an act of unspeakable violence. The story Gross tells echoes here in Żychlin and many other towns across Poland—places once filled with Jewish life, now emptied of memory, unless someone comes to uncover it. https://amzn.to/3Ixc0rK

Tomorrow, on Day Three, we’ll begin with a sobering visit to Chełmno—the extermination camp where most of Żychlin’s Jews were murdered and incinerated for the simple “crime” of being Jewish.

Please follow the The Matzevah Foundation, Inc.